April 21, 2021 (New York, NY) – FJC hosted a webinar to highlight its strategic partner the Cultural Heritage Finance Alliance (CHiFA), a new initiative that promotes heritage-led regeneration through collaborative and innovative financing solutions. The event was moderated by Sam Marks, FJC’s Chief Executive Officer and highlighted two promising examples of organizations that embody CHiFA intends to support: Doh Eain and Turquoise Mountain.

A full recording of the webinar is available at this link.

“Our goal is to bring the public sector and private sector together in joint initiatives.”

Bonnie Burnham, Co-Founder, CHiFA

Mr. Marks kicked off the event by explaining FJC’s role providing operational and fiscal support to CHiFA. As a foundation of philanthropic funds that brings economies of scale to philanthropists (by sponsoring Donor Advised Funds) and organizations (through fiscal sponsorship), FJC will provide operational and administrative support, including servicing CHiFA’s loan fund. CHiFA is currently raising $3 million to provide catalytic, early stage capital to heritage regeneration projects around the world. With FJC administering the loan fund, CHiFA will be able to stay lean and focused on mission.

CHiFA Co-Founder Bonnie Burnham described how CHiFA evolved out of her many decades of experience at the World Monuments Fund. Her previous work was largely focused on revitalizing individual sites, using philanthropy to leverage public sector. Her work at CHiFA has a more intentionally broader economic and social impact in mind, through nonprofit partners that facilitate investments in enterprises and the urban fabric. “We’re trying to create a methodology that can be widely applied,” Ms. Burnham explained. “Our goal is to bring the public sector and private sector together in joint initiatives.”

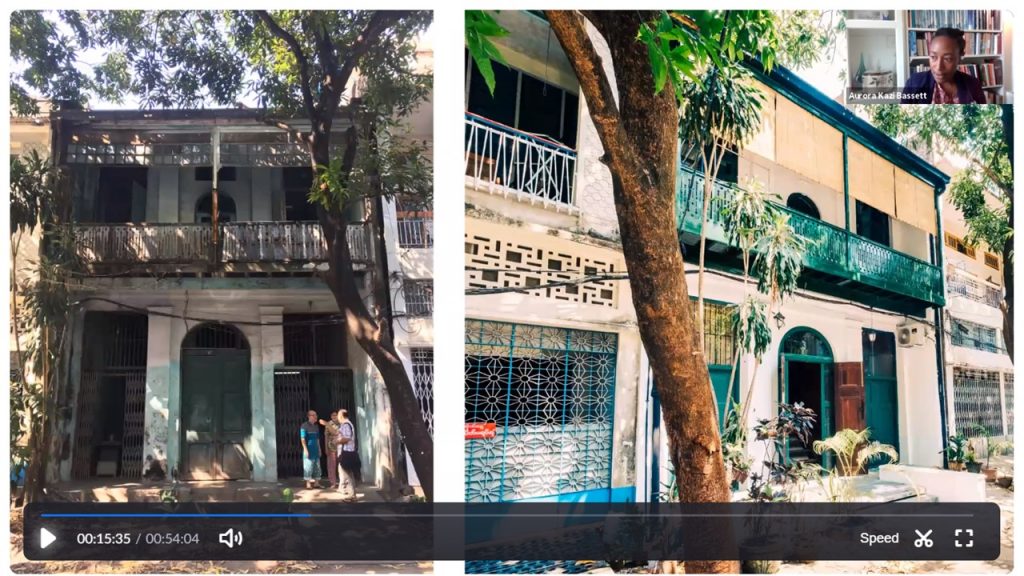

Aurora Kazi Bassett, the Director of Outreach & Policy for Doh Eain described a promising model of the type CHiFA has in mind: her organization’s work in Yangon, Myanmar. Doh Eain is a social enterprise that uses private investment (and some grants) to restore and maintain small and medium sized, privately owned historic residential buildings, and also improve public spaces that can be used by the community. “These are not the big, beautiful palaces that we go to visit on holiday, but the shops, houses, and office buildings that have been used by normal people’s homes.” Doh Eain’s model does not purchase the properties outright, but takes on the risks of revitalization during a discrete leasehold period and returns ownership back to the original owner-residents.

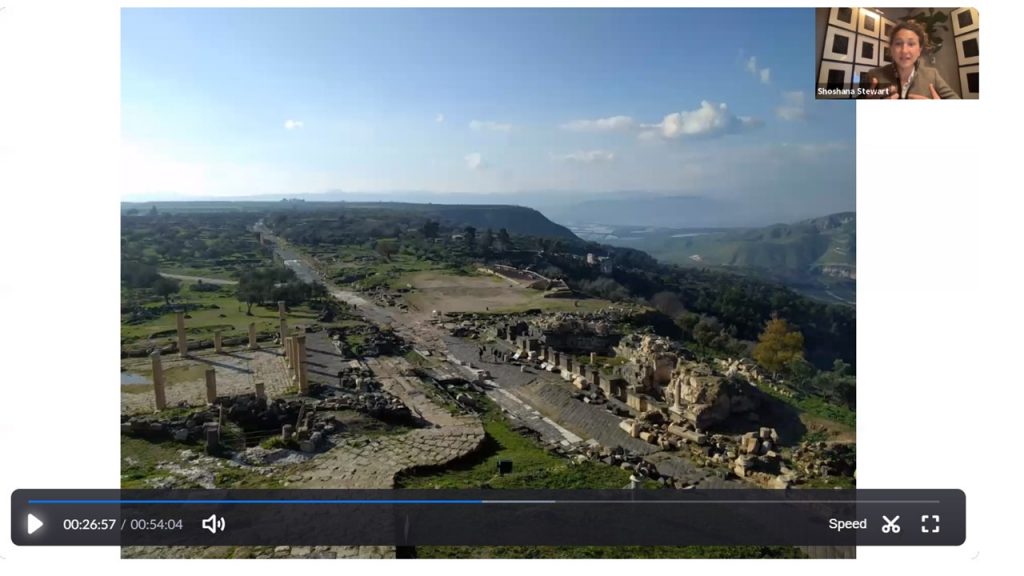

Shoshana Stewart, CEO of Turquoise Mountain, presented another model of heritage-led regeneration. After describing some of the organization’s successes in the Old City of Kabul, Afgahnistan, Ms. Stewart described their vision for Umm Qais in Jordan, a unique architectural site at the crossroads of the Middle East, adjoining Syria, Lebanon and Israel. With layers of architectural and cultural assets, including Roman ruins, Byzantine period mosaics, and a ruined Ottoman period village, Turquoise Mountain intends to leverage tourism, which a cornerstone of country’s economy. “Typically when international tourists come, they come to the big sites: Petra, the Dead Sea, Wadi Rum. In the north of Jordan you’ve got a number of sites, but there is nowhere to stay. If we can get the accommodations right, we have the potential for both international and domestic tourists. There’s significant potential.”

Common across the Doh Eain and Turquoise Mountain examples is an enterprise model that combines some philanthropic grant resources with more conventional investments that offer a return to investors. In Doh Eain’s case, rental income from the residential and commercial, properties covers the cost of the physical revitalization, and also provides an income stream to the building owners and a return to impact investors. Doh Eain uses some of the profits, along with grants, to implement public space work that is more purely subsidized. Turquoise Mountain will seek investment capital to develop the ruined Ottoman village into accommodation (which will ultimately generate revenue). Simultaneously, they work with a range of grantmaking partners, including development agencies and philanthropy, for the pieces of the project that are critical to its ultimate success but not expected to generate revenue.

In advance of their capital raise, CHiFA has documented the emergence of heritage regeneration NGOs with investable business models in their recently published white paper Impact and Identity, Investing in Heritage for Sustainable Development. Says Ms. Burnham, “We have to convince impact investors that heritage is a missing link in the circular economy strategy, bringing human environments into compliance with meeting our goals for sustainable development. This is where there’s a tremendous opportunity.”